|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Suicide Tactics: The Kamikaze During WWII |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Gerald W. Thomas, VT-4 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On December 7th of each year the United States celebrates Pearl Harbor Day. This recognition of "a day that will live in infamy" usually results in a number of excellent documentaries and articles about Pearl Harbor and WWII. Many people point out similarities between the shock of December 7, 1941 and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. There are indeed some similarities between these important dates in our history: both events were complete surprises; both events cost many lives; and both events united Americans against an enemy. In WWII, the enemy was easy to define and locate. Not so after 9/11/01. The enemy is now difficult to locate and even more difficult to identify. There is another similarity with these two wars—fanaticism and suicide tactics. While Japan apparently did not use suicide tactics at Pearl Harbor, we know of their use of the Kamikaze later in the war. One historian stated that by the end of WWII:

Although there may be some question about the exact numbers, the damage done by Kamikazes is almost unbelievable. And the losses would have doubled or tripled if the invasion of the Japanese mainland had been required for surrender. All indications are that suicide tactics would have been an important part of the final Japanese defense. I had three rather personal experiences with suicide bombers in the Pacific. I know something of the fear and panic that is generated when Kamikazes approached our Navy Task Force. I saw our ships' gunners so jittery by the presence of Kamikazes that they fired on our own planes returning from strikes on Japanese targets. On November 20, 1944, while the Task Force was anchored in Ulithi Lagoon, at least two Japanese mini-subs slipped through the submarine nets and entered the harbor. One of these subs, a Kaiten manned suicide torpedo with a 3418-pound warhead struck the USS Mississinewa, an oil tanker. The ship exploded in flames and soon sank with a loss of 63 sailors and the Japanese pilot.

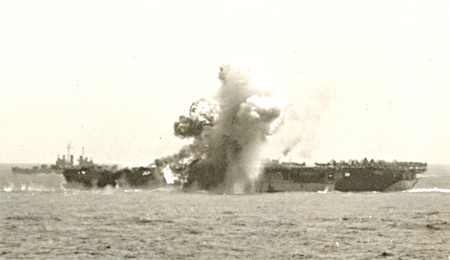

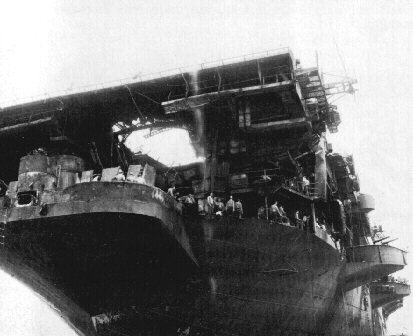

My closest call from a Kamikaze occurred on November 25, 1944 while aboard the USS Essex. This was a particularly rough day for our Task Force -- we fought off swarms of Kamikazes and had 4 aircraft carriers hit in a one-hour period:

From post-war research using photos of the Japanese plane, a Yokosuka D4Y3 dive bomber, we have learned the name of the Kamikaze pilot. He was Yoshinori Yamaguchi from the Yoshino Special Attack Corps stationed at Malabacat Field in the Philippines.

My next experience with suicide planes was on the night of March 4, 1945. Our Air Group was in Ulithi Lagoon being loaded on the USS Long Island for return to the States. Since Ulithi was a long way from the nearest active Japanese base, all ships were well-lighted. I was on the flight deck of the Long Island visiting with G. D. "Mak" Makibbin, a fellow torpedo pilot. We were talking about the trip home when we heard two planes overhead. These planes had a different sound—a noise that we did not recognize. We speculated out loud about this new type of plane when one came very close and actually flew into the flight deck of the USS Randolph anchored next to us. There were at least two explosions and a fire. Mak and I ran around the flight deck trying to kick the lights out on the flight deck of the Long Island—anything to prevent a further attack by what was obviously a Kamikaze. A few minutes after the first plane dived into the Randolph, a second plane dived into the ground on a nearby island—probably mistaking the lights for an aircraft carrier. We learned later that the second plane did not do much damage, but made a sizable hole in the ground. The Randolph was burning, more explosions followed, sirens sounded, and all ships in the Lagoon were ordered to General Quarters. The Kamikaze had taken the lives of 25 men and severely wounded 106. An examination of the wreckage showed the pilot to have been shackled to the cockpit.

As we were returning to the States in May 1945, we were ordered not to mention the word "Kamikaze" or to mention damage caused by these suicide tactics. The Navy did not want US citizens to know the extent of damage, nor did the Navy want the Japanese to know how effective these tactics were. We have similar challenges today. An interesting aspect of the Kamikaze story, particularly as it relates to "motivation to commit suicide" is in the following post-war report by Higher Flight Officer Motoji Ichikawa: "Suddenly the voice of the Officer of the Day broke through the perpetual static of the barracks public address system. 'All pilots line up in front of headquarters.' As soon as they were in formation, the Wing Commander without preamble shouted, 'All those men who are only children raise your hands.' Puzzled, these men were ordered to return to the barracks. 'First sons also break ranks and return to your quarters.' The Wing Commander ordered the remaining men to form a circle in front of him. He stated that the war news was very bad. 'We must, therefore, somehow mount an offense that will bring excruciating pain to the enemy. To achieve this, we have developed a new and special instrument of certain death. But, in order for this kind of special attack to succeed, the weapon has been designed as a one-way trip.' The Wing Commander then told the pilots they had to choose to take a one-way flight by writing 'Yes' or 'No' on their ID card and dropping them in a special box." Ichikawa was tempted to write 'No,' but he knew he could not. He knew he would be condemned as unmilitary, as unmanly, if he were to refuse. So he wrote the 'Yes' on his ID card. Through a combination of circumstances, Ichikawa survived to tell his story. A logical conclusion to this article is to pose the question, "What can we learn from the Kamikaze experiences of WWII that will help us face the potential for more suicide attacks as a terrorist strategy?" References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Air Group 4 - "Casablanca to Tokyo" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||