|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Few Things Remembered about Air Group 4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Lloyd E. Edens, VB-4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

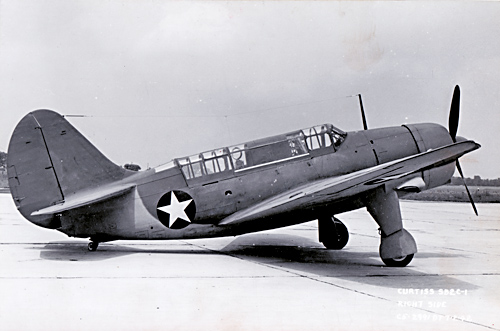

The planes were the Vought Sikorski Vindicators: two seaters, partly fabric, single-wing dive-bombers. I was assigned a plane; they said I was supposed to maintain the radio equipment and fly in the back seat whenever it took off. I had no idea as to what I was doing. The school I went to in Norfolk (it was called Advance Aviation Radio School) taught us nothing about working or flying in these type airplanes. We spent most of our time taking Trigonometry, studying radio theory and practicing Morse code on a typewriter. Had to copy 32 words per minute to graduate. After I left school, I never used a typewriter, and never had to copy code, except for blinker lights between planes and the carrier. Of course that was no 32 words per minute. So I was totally unprepared to jump in a dive bomber and come screaming straight down from 20,000 feet and watch to see if our smoke bomb came anywhere near a target being towed behind the Ranger. About the only piece of equipment I felt qualified to handle was the pee tube, and I wasn't quite sure about that!

Suddenly, without warning, we were told to move back to the carrier. We thought we were going back to the States. Once on board and underway, the Captain of the ship announced on the intercom that we were on our way to Casablanca to participate in the invasion of North Africa. Now if that wasn't enough to throw a scare into a greenhorn, I don't know what was. So we spent the next 4 days flying anti-sub patrols and being briefed on what we would be doing in Casablanca.

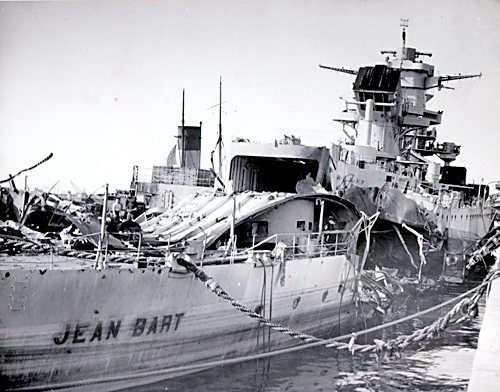

We were also supposed to bomb a group of about 13 German U-boats tied up to a dock. Unfortunately, we did not get them all, because a few days later the Ranger was surrounded by U-boats firing torpedoes at it. I will never forget that day. The captain had the men who were not assigned a gun station to stand on the catwalk and watch for torpedoes. Every time one was spotted someone would yell out and a guy on the intercom would relay to the bridge. The captain would then turn hard to port or starboard, depending on which side of the ship the torpedo was come from. It's hard to believe how well they were able to turn and make the torpedoes miss us. One torpedo struck the USS Augusta, but it was a dud. After a while the destroyers eliminated all of the subs and we went back to flying missions again. The first time we came down on the Jean Bart, which was my very first combat mission, I could not believe we could get through all of the anti-aircraft fire that was thrown at us. The tracers seemed to be everywhere, and the little black puffs of smoke from the exploding shells were all around us. Amazingly enough, we didn't get shot down and we were able to drop our 1000 lb. armor piercing bombs. We bombed this battleship for 7 days, and it finally was sitting on the bottom at the dock. On the last day we were flying rather low near the battleship and some die-hard sailor was shooting at us with a 30-caliber machine gun from the deck.

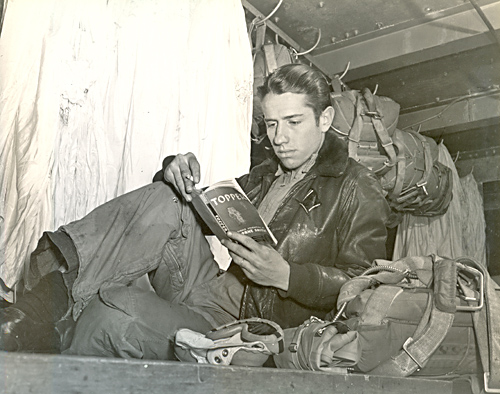

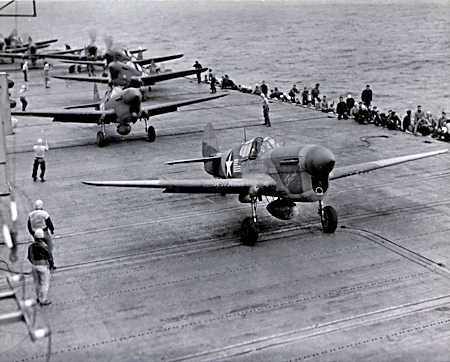

One of my sadder memories was when one of our radiomen came back to the Ranger dead. He had been hit in the knee with an anti-aircraft shell and apparently bled to death. That hit us all pretty hard, especially since this was our first taste of combat. (See Ranger Air Group over Casablanca - OPERATION TORCH and "Bring Back the Handles.") More Memories of the Ranger and Air Group 4 After that little skirmish described in the section above, we sailed back to Norfolk, and the Air Group moved onto the Naval Air Station there. The planes were put in the hangar and opened up for inspection. We found some of the anti-aircraft bullets inside the wing. On one airplane a 50-caliber bullet was stuck in a torque tube which was connect to the ailerons. During the fighting, when we returned to the carrier, the deck crew would cover up the shrapnel and bullet holes with metal tape, and send us back out. I have decided in my old age that it takes young men to fight a war, because they are more daring and have the feeling of being indestructible. I did things then that I would never even think of doing today. After getting all our planes back in good shape we went back aboard the Ranger and sailed up to Quonset Point. From there we went to the waters around Newfoundland. It was while we were there that the German U-Boat commander claimed they had sunk the Ranger. (For details, see Von Bulow Decorated for Sinking USS Ranger.) We were all sitting on the hangar deck one evening watching a movie, and they announced on the intercom that we had just been reported sunk. The AP wire service report said that all of the planes were destroyed and that flames shot hundreds of feet in the air. In other words they were really giving a vivid report of our demise. The captain ordered the photo lab to make Mother's Day cards to send to our mothers to ease their mind about us being sunk. I believe they had written on the card ... "Don't believe everything you see in the papers, Happy Mother's Day." About the time we were in the Newfoundland area, the Navy came out with a new piece of electronic equipment called IFF (Identify Friend or Foe) which would send out coded signals so the ship could tell if we friendly or not when we approached the task force. Well, each of us was given the responsibility of installing this equipment in our assigned airplanes. This black box was about 12 by 18 by 12 inches in size and was to be shock mounted in a compartment just aft of the rear seat. An inertial switch that would ignite an explosive was built into the black box to destroy it in case we crashed in enemy territory. This explosive was not real strong, but just enough to melt everything inside the unit. So as we were installing this unit we suddenly heard small explosive charges going off each time power was put to the unit. Boom here, boom there and boom over there. It seems that the wiring diagrams for installation had some wires crossed and the explosive devices were activated the minute power was applied. It took a few days to get some new equipment with the correct wiring diagram supplied. The next trip to Africa was to deliver Army Air Corps P40s. Most of the Air Group stayed in Norfolk, but left on board were enough planes to do anti-sub patrol. I was one of the ones to stay on board. While flying a boring 4 hours on anti-sub patrol, some of the SBD pilots would let the radioman fly from the back seat. We had a removable stick and rudder pedals, throttle, and only the most basic instruments, i.e. altimeter, airspeed, and turn and bank indicators. We always had 4 airplanes flying in the 4 quadrants of the carrier. Well, one day I was flying from the back seat trying to maintain altitude and airspeed when suddenly the stick was yanked out of my hand and we nosed over abruptly. A second later another SBD skimmed over the top of us, barely missing us. I obviously was not maintaining our assigned quadrant, and I could not see forward very well. Thanks to my pilot being alert, I am still here to tell about it. The Air Corps pilots were so very young. They had just finished transition training in the P40 before coming on the Ranger. Needless to say, the Navy pilots had a lot of fun with them, telling them a few horror stories about flying off the carrier deck. In spite of the Navy pilots, they all made it off OK. A few of them dipped down after leaving the end of the flight deck and we all kept our fingers crossed until we could finally see them pulling up over the deck. After they were all airborne, they flew past the carrier in formation at flight deck level. It was quite spectacular.

Quite an interesting trip after all. We all thought it was going to be boring. But then, most of our trips on the Ranger were interesting. More Adventures in VB-4 It was a dark and stormy night... Nah, it was a nice clear night in the waters around Newfoundland. Air Group 4 was chosen to make carrier landings at night for the first time in naval history. Lights were installed on either side of the flight deck. They were recessed in the deck, and were oriented toward the fantail. They were not visible to other ships in the area, but the pilots could see them when they turned on their final leg and lined up with the carrier. There were some lights that could be seen by other ships (or U-boats). There was a single white light on the top of the main mast. One of the lessons learned during these experimental night landings was the carrier should have a different type of mast light, because the pilots had a difficult time determining which of the lights was the Ranger. One pilot tried to line up to make a landing on the USS Augusta. So they put a single red light on the carrier and left the rest of them white.

One of the pilots must have become disoriented during the take-off because he flew right into the water as he left the flight deck. You know how they always said they would not risk the carrier and other ships to try to find someone in the water at night. Well, they did take the risk and turned on searchlights so a destroyer could pick up the pilot. That was the only mishap that occurred, however, and Air Group 4 did prove that night carrier landings could be made. Of course, that was the last time we did night landings, but the group proved it could be done, and that was some accomplishment. Shortly after the Von Bulow incident, the Ranger was assigned to the British Admiralty. The Ranger went into dry dock at Glasgow, and we were given a 7-day leave. Most of the guys wanted to go to London, so we got on a train and headed South. The trains were all standing room only, and in some cases the standing room was between the cars. It took all night to make the trip, and we slept most of the next day. Roamed around London later and had to visit the bomb shelters several times. One of the guys heard about a place where they had a big ballroom and changed dance bands every hour on a rotating platform. We found our where it was and found our way to a place called Covent Gardens. What a place! There was an abundance of buffet food, and a dance floor that seemed to be about 5 acres across. The music was fabulous and there sure was not a shortage of girls to dance with. My first trip to London, and enjoyed every minute of it. By the time we got back to Glasgow, the Ranger was ready to go. We were sent up to the Orkney Islands, specifically, to a place called Scapa Flow. We were there to try to get the German warships that were hidden up against overhanging cliffs. There was no way to drop bombs on them from above, so the British had us practice "skip bombing." You know, like skipping a flat rock across the river. Fly low and head for a target, and just before passing over the ship, drop the bomb. The theory was that it would hit the water and skip a couple of times until it hit the ship at the water line. Surprisingly enough it worked.

There was an interesting rivalry going on between the F4F pilots and the British Spitfire pilots. They decided to have a mock dogfight between them. With all due respect to our fighter pilots, the F4F was no match for the Spitfire. Every now and then the German ships would go out to sea, and the Air Group would scramble back to the carrier from the Naval Air Station and we were off to sink the German Navy. The carrier task force was shortly spotted by German scout planes, and the German Navy would turn back to the protection of the fiords. Likewise the Ranger would go back to Scapa Flow. This went on a couple of times, before we finally were detached from the British Admiralty and went back to the States. In December 1943 we returned to Quonset Point. In April 1944 we moved to Ft. Devens, Massachusetts. It was here that we traded in our SBDs for the SB2C Helldivers. The SB2C sure seemed like a large airplane compared to the SBD, but that was because it was a larger airplane. It was faster and had a larger payload. We traded our twin 30-cal machine guns in for one 50-cal in the rear seat.

After a sojourn in Ft. Devens, the Air Group was put on a special cross-country train that took us all the way to San Diego. What a lousy train! All enlisted men below the rank of First Class Petty Officer rode in open cattle car type accommodations. The others rode in a closed Pullman type car. This was especially nice when we were crossing the desert in New Mexico and Arizona. We finally arrived in San Diego after several days (I can't remember how many), and boarded a baby flat-top for transportation to Hawaii. We arrived in Hilo in July 1944, and spent several glorious months basking in that tropical paradise. It rained every day about 1:00 o'clock for about 10 minutes, then the sun came out. Oh, it was lovely. We spent a lot of time training to recognize Japanese planes and naval ships, and we spent a lot of time practicing bombing with smoke bombs in Hilo bay. Someone came up with the idea that we could gain about 10 knots of speed if we waxed the airplanes. Obviously that someone was not going to have to do the waxing. So we spent a lot of time waxing the SB2Cs. That was when I realized how big the Helldivers were. But I really couldn't complain; there we were living in paradise and getting paid for it. Wow, can't beat that with a stick. We left Hilo in October 1944 to join the Task Force 58 in the 3rd fleet, in a far-off place we had never heard off, called Ulithi. After you get there it is easy to see why no one has heard of it. It is a ring-shaped coral island (I think they call them atolls) that provides a very nice harbor. This is where the fleet rested, re-supplied and licked its wounds when it came off of a mission. There really wasn't anything on the island to do. The one time we had shore leave it consisted of riding a motor launch to the island and sitting on a coral rock in the scorching sun drinking beer that was brought ashore for that purpose. Those of us who did not drink beer were treated to a can of Coke. What a blast. Anyway, Air Group 4 was deposited on the USS Bunker Hill A Short Tour on the USS Saratoga Before leaving Hawaii for the 3rd Fleet, we took part in a mock attack on Pearl Harbor. We took off from the USS Saratoga and as we flew to Pearl, we were met by interceptors from the Air Corps. One of them came up from beneath our flight and collided with the Hellcat flying on our wing. Everything happened so fast that all I remember seeing was the engine of the Hellcat going down in a ball of fire. Our maintenance Chief was on that plane, although he was not a regular air crewman. I don't remember why he took the flight, but he was not normally scheduled for it. After a long journey, we finally arrived in Ulithi and moved our planes and gear aboard the USS Bunker Hill. Quite a difference for Air Group 4, which had only seen carrier duty on the Ranger. Before long we were on our way to the Philippines where we made several bombing missions to bomb shipping in Manila Bay and to bomb Clark Field. Saw a few Zeros, but none actually attacked the missions I flew on. We would see them following us to try to find the carrier, but our fighters would go back and take care of them. After about a month on the Bunker Hill, a message was sent out to all ships wanting to know where Air Group 4 was. It seems that we were supposed to have relieved the air group on the USS Essex, and we relieved the one on the Bunker Hill by mistake. So off we went to the Essex. While at anchor in Ulithi, a Japanese 2-man submarine was discovered and captured. The 2 Japanese crewmen were brought aboard the Essex. As they arrived at the bottom of the ladder to come aboard, they were met by the Marine company attached to the carrier, and the two Japanese began to bow deeply, begging the Marines not to harm them. We found our later that the word out among the Japanese sailors was that the Marines didn't take prisoners, and these two thought they were going to be killed immediately when they saw the Marines. The Kamikaze Event It has been demonstrated many times that when several eye witnesses are asked to describe what they saw after an event, each one would have a little different story to tell. Of course it depends upon where the person was at the time of the incident and from which angle they were observing. With that in mind, here is what I remember about the suicide plane hitting the flight deck. My pilot Lt. [William H.] Longley and I were in our Helldiver with the engine running, getting ready to take off on a mission. Suddenly, the carrier's anti-aircraft guns on both sides of the ship started firing. I saw one Japanese plane coming in from the starboard side, and one coming in from the port side. Both of these were shot down by the carrier's gunners. A third one was coming from the rear of the carrier. This one flew right over our plane and hit the deck, I thought, just forward of our normal rev-up spot.

Others may remember differently, but that's my story and I'm sticking to it. There is one thing for sure, it sure scared the hell out of me. (See Suicide Tactics: The Kamikaze During WWII.) The Big Typhoon I remember riding out the typhoon in the Ready Room all night. The ship would list to one side and the other, often 45 degrees. Unfortunately we lost several ships in that storm. It was in December of 1944, and one of the ships that went down had all of the Christmas mail aboard. This, of course, was nothing compared to the lives that were lost. What a tragedy (See Halsey´s Typhoon.)

Speaking of new equipment, I remember the first radar we had installed on the SBDs while we were in Newfoundland. This was most primitive by current standards. We had two Yagi antennas mounted under each wing tip. We could rotate these antennas with a mechanical control lever from straight forward to 90 degrees to the port and starboard. The indicator was a cathode ray tube with a vertical baseline up the middle. The baseline was fuzzy on either side, which we called "grass." When the radar beam received a return echo from a ship, or other reflecting surface, a "blip" would appear along the baseline. The further the blip was up the baseline, the further away the ship was. Thus, we could measure the distance to the target along the vertical line. Not very sophisticated, but it worked. I always thought it interesting that the antenna we were using was invented by a Japanese, thus the name Yagi. This is basically what our present local TV antennas are. After several months on the Essex, it was decided that the Marines would take the place of VB-4, so the squadron flew off to Guam, where we lived in tents. We did very little flying during this visit to Guam. This was in January and February of 1945. (See War Diary of Two Marine Squadrons -- VMF-124 and VMF-213 Aboard the USS Essex.) After leaving Guam, the squadron was broken up and we all went many different ways. For lack of any place else to send us, the air crewmen were sent to Norman, Oklahoma to gunnery school of all things. I spent a couple of months there, and was then transferred to temporary duty in Corpus Christ, Texas. The Navy was never the same after leaving Air Group 4. We were all rather disheartened over the situation. I was finally transferred to Banana River Naval Air Station in Florida. I flew as plane captain and radio operator on R4Ds, the Navy version of the DC-3. After more than 5˝ years in the Navy, I was finally discharged on December 14, 1946. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Air Group 4 - "Casablanca to Tokyo" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After completing a five-month course in Aviation Radio in Norfolk, Virginia in 1942, I was assigned to a dive-bombing squadron (they called it a Scouting squadron then) which was at that time currently aboard the USS Ranger. It was at sea at that particular time so I went to Boston and stayed in a Receiving Station, which was a converted warehouse in downtown, for one month. This was probably the most leisure time I ever spent in the Navy. The food was out of this world. Fresh fruit at breakfast, eggs fixed to order, pancakes, you name it. This was almost continuous shore duty. Then the ship arrived at Quonset Point, and I went aboard. A total "greenhorn."

After completing a five-month course in Aviation Radio in Norfolk, Virginia in 1942, I was assigned to a dive-bombing squadron (they called it a Scouting squadron then) which was at that time currently aboard the USS Ranger. It was at sea at that particular time so I went to Boston and stayed in a Receiving Station, which was a converted warehouse in downtown, for one month. This was probably the most leisure time I ever spent in the Navy. The food was out of this world. Fresh fruit at breakfast, eggs fixed to order, pancakes, you name it. This was almost continuous shore duty. Then the ship arrived at Quonset Point, and I went aboard. A total "greenhorn."