|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Airmen Missing in Action (MIAs) and |

|

By Gerald W. Thomas, VT-4 |

|

|

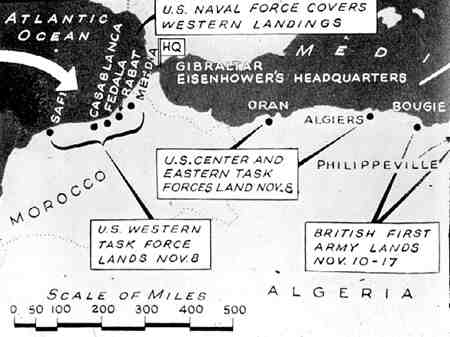

Air Group Four During World War II During World War II, airmen from Air Group 4 were lost in operations or combat in both the Atlantic and Pacific Theaters of War. Some were listed as "Missing in Action." Others became prisoners of the Germans or Japanese (POWs). Some survived the war. This is a partial report on 61 of these airmen based upon combat reports, journals, and post-war information. OPERATION TORCH Early in the war, the USS Ranger was stationed in the Atlantic with the primary mission of anti-submarine patrol. The first actual combat for the Air Group was OPERATION TORCH, an invasion of North Africa.

The Vichy government in North Africa capitulated on November 11, 1942 and these Ranger airmen were released to return to the Air Group or to other assignments. OPERATION LEADER The next engagement of Air Group 4 against the Germans was OPERATION LEADER. This involved strikes on German shipping along the Coast of Norway, mostly north of the Arctic Circle.

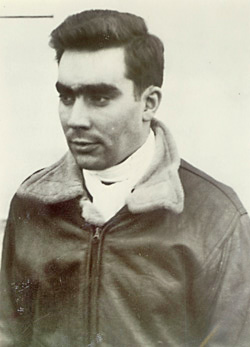

Lt(jg) John H. Palmer, VT-4 Lt(jg) John H. Palmer's TBF Avenger was shot down by German AA fire on October

As the unofficial historian for Torpedo Four after the war, I tried to locate John Palmer to obtain his version of the strike and his capture by the Germans who were occupying Norway. Finally, in 1988, I learned that a former P-51 pilot, Richard Lucas, had been in the same German prison camp and he knew John's current address. Lucas gave me a phone number, which led to a reunion after 46 years. At this meeting with John and his wife, I presented a plaque to John that contained parts of his plane salvaged by the Norwegians. The salvage of Palmer's TBM was initiated by Steinbjorn Mentzoni, then a 9 year old boy, who observed the crash (see Norway: A Grateful Nation Remembers). John Palmer's comments on the crash and POW experience follow. I must have caught a shell right through the back of the plane; it went right under me and into the engine, because it caught fire. I think it must have killed Zalom and Miller. I called them on the intercom trying to get them to get out, but received no answer, so I jumped…. After I hit the water and got loose from my parachute, I swam to shore and waded right into this antiaircraft station. I had hailed some fishermen, hoping to get picked up, but had no luck. The Germans took me as a prisoner and moved me to Oslo, Norway. After a week in Oslo, the Germans transferred me to Frankfurt for a week of interrogation on bread and water, and then took me to Staleg Luft Three. I was the only Navy guy in this camp, and I found the other prisoners ignored me completely for about 2 weeks…, they thought I was a German plant. They showed me a German newspaper, which said the Ranger had been sunk in September…. Of course, I told them that I was off the Ranger, and they didn't believe me. They believed the newspaper (see Von Bulow Decorated for Sinking USS Ranger). Several other comments by John Palmer are worthy of note: We were flying at 1500 feet. The flight flew right over this AA battery which was not mentioned during the preflight briefings. I became well acquainted with John Dunn, the first American prisoner in the camp. Dunn was a graduate from the Naval Academy, but he made a navigation error on a return flight to Scapa Flow and ended up in Norway. I roomed with Dunn and we learned a British Code (like a Boy Scout Code) and we interrogated every new prisoner who came into the camp. The Germans let the Red Cross send in clothes, books and games, and the YMCA sent us some musical instruments. We were allowed to write 2 letters and 3 post cards per month. The Germans seemed to have more respect for the Navy guys than the other POWs. We were liberated by the Russians and spent 2 to 3 months living off the country before an American unit took us in. I was sent back to Pensacola for a refresher and then the atomic bomb ended the war. I got out of the Navy in September 1945. Somehow, my log book was returned to me with comments by Lee Hamrick and Felix Ward (See Memories for an account of how Palmer´s log book was preserved). Mr. Alf Larssturold of Bodø, Norway has acquired a copy of a photo of Palmer taken shortly after he was captured by the Germans. This photo is by Walter Henkels, a well-known German photographer who made a career for himself as a journalist in West Germany after the war. Mr. Larsstuvold also sent a transcribed copy of the interrogation of Palmer after his capture. As expected, the Germans attempted to gain as much information as possible from him about the Task Force, the Ranger, and the aircraft component. In a concluding statement, the interrogator reports that, "The POW…loves German music (Schumann), has trained as a singer, and has often performed at a Swedish Club in Chicago." (Translation by Mr. Larsstuvold.)

|

|

|

|

After my initial contacts with John Palmer in 1984, I informed the family of Reginald Miller in Florida and Steinbjorn Mentzoni in Norway of his address and phone number. Jack and Lou Miller, with the help of Mentzoni, had been very involved in the special ceremony in Fagervika, Norway on October 4, 1987 to recognize the loss of Zalom and Miller, Palmer's crew members. The Millers also made arrangements for an additional memorial ceremony at the Naval Air Museum in Pensacola, Florida. This recognition to those lost in OPERATION LEADER was held on October 6, 1990. John Palmer and his son were present for this Ceremony. At the ceremony in Pensacola to honor Palmer's two lost crewmen (Zalom and Miller), one blade of Palmer's propeller salvaged from the sea was presented to the Naval Air Museum. One blade had been previously incorporated in the Memorial at Fagervika, Norway. The third blade of the prop of the doomed Avenger remains in the Home Guard facility at Sandnessjoen, Norway. |

|

|||

|

Monument to honor airmen lost in OPERATION LEADER |

|||

|

Lt(jg) Sumner R. Davis, VB-4 Lt(jg) Sumner Davis was also shot down by German AA fire. Davis was flying an SBD Douglass dive bomber with D. W. McCarley ARM2c as gunner. The plane was hit during an attack on the ship "Rabat," anchored outside Bodø Harbor. Davis ditched his damaged SBD near the small island of Prestoya by the Helligvaer islands. He and McCarley managed to inflate and climb into a small rubber raft. The raft was spotted by Norwegians Odd Karlsen and his father, who were fishing nearby. They took Davis and McCarley to their home. Odd Karlsen stated, "The Germans had seen the crash and had lookouts everywhere-and also the fact that we were in small islands away from the mainland-there was little we could do." Germans soon located the Americans and took them as prisoners of war. In a letter to John Carey published in the USS Ranger (CV-4) News, Sumner Davis relates his experiences as a POW:. |

|

|

Fifty years after OPERATION LEADER (October 4, 1993), Odd Karlsen (now 75) met Sumner Davis (also 75) as Davis walked into the airport at Bodø, Norway. The two men shook hands and embraced. Davis did not understand Norwegian. Karlsen did not understand English. Words seemed unnecessary. It had been 50 years since Odd Karlsen and his father (now deceased) had rescued Davis and McCarley from the Norwegian Sea after their dive-bomber was shot down by German anti-aircraft fire. Before the Germans took the two American airmen as prisoners, they were taken care of by the people of Helligvaer. Morten Gryt was called upon to translate, because he spoke English. Sumner Davis took off his watch and his ring and gave them to Morten Gryt's wife, Elsa. Elsa still had the ring and the watch after 50 years. She said to Davis, "It is important to hand the ring and the watch back." During this meeting in Norway after 50 years, Odd Karlsen insisted on taking Sumner Davis for a boat trip to the place where his plane went down. As the two reacted, Davis said, "You and your father did what you could. You saved my life. I will never forget that." It was a touching reunion. Newspaper Article, Nordlandsposten, Bodø, October 2, 1993 |

|

|

POWs and MIAs: The Pacific Theater of Operations Pilots and crews in Air Group 4 were more concerned about being captured by the Japanese than by the Germans. Stories of torture and mistreatment were rampant. In addition, we were warned that if we were captured and revealed any critical military information, we would be severely punished. (See A Question of Security in Torpedo Squadron Four: A Cockpit View of World War II.) To avoid capture, every pilot was told, "If you are hit over land, try to stretch your glide path to reach the water. Keep away from shore! If a rescue sub or picket destroyer has a position report on your location, a rescue will be attempted." Selected reports on downed airmen from Air Group 4 flying from the USS Bunker Hill and USS Essex with dates and locations are listed here. Quotations are from debriefings in the US Naval Archives unless otherwise noted. (1) November 13, 1944: Lt(jg) A. F. Summer and gunner ARM2c George Bogel (VB-4). Shot down during a strike on Cavite, Luzon. "He and his radioman were successful in inflating their life raft." No post-war reports are available on capture or survival. Note: Summer and Bogel survived the crash of their plane and were picked up by Company L, 3rd Bn, Hunters-ROTC Guerrilla group, code-name "Sierra Reno," commanded by 1st Lt Catalino del Rosario. In an affidavit of his war-time service filed after the war with the Municipality of Naic, Province of Cavite, 1st Lt del Rosario stated: "From Oct. 14 to Nov 1944, he helped the rescue and care of US Army Flyers, Lt. Summer, Lt. Chester Knosech [Chester Knozek], & Gunner Bogil [Bogel]." Document provided by Mr. Timothy Prickett. Mr. Prickett's wife's grandfather served in the Sierro Reno Filipino guerrilla unit. (2) November 13, 1944: Lt(jg) Arthur G. King, Jr. and ARM3c Richard A. Smart (VB-4). Hit by AA fire over Manila as he pulled out of the dive. Listed MIA. No post-war reports of survival. (3) November 13, 1944: Ens. James I. Hawkins and gunner ARM3c G. P. Curtice (VB-4). Plane last seen prior to pushover on shipping in Manila Harbor. Listed MIA with no post-war reports. (4) November 13, 1944: Manila Harbor. Ens. William N. Ostlund (VF-4) "… not seen after the dive. It is believed that his plane was hit by AA and he crashed." Listed MIA with no post-war reports. (5) November 14, 1944: Manila Harbor. Ens. Kenneth W. Watkins (VF-4) "Was hit by AA fire and crashed in flames." Listed MIA with no post-war reports. (6) November 14, 1944: Lt.(jg) Donald Dondero and ARM3c Chester Knozek (VB-4). "Dondero's plane was hit by AA fire, and two persons were observed to bail out hitting the water between South Manila Harbor and Cavite. McReynolds saw one person in a life raft, and one in a life jacket. Their chances of being picked up by 'friendlies' were minimal." This official report did not take into account the determination and imagination of there two airmen. Both Dondero and Knozek managed to bail out of their burning Helldiver, evaded capture during a several day ordeal, and eventually return to the US. (See Dondero and Knozek Bail Out Over Manila Harbor.) Knozek was rescued by the "Sierra Reno" Hunters Guerrilla group, as noted in the Summer/Bogel report (1) above.

(8) November 25, 1944. Lt(jg) Russell L. Deputy, VB-4, was killed when his Helldiver crashed on takeoff. I recorded in my journal: "Two Helldivers went in the drink while VT-4 was turning up on the fantail (the VB-4 skipper, Lt Cdr Johnson, and Lt(jg) Deputy. Johnny and his gunner got out of the plane, but Dep was never picked up)." (9) November 25, 1944: Ens. Billy Nye Kinder and ARM3c Donald R. Follweiler (VB-4). "In a strike on shipping in San Fernando Harbor on November 25, 1944, the Helldiver piloted by Ens. Kinder was hit by AA fire and went down in the bay. We believe there were no survivors but the two were listed as Missing in Action." (On November 25, 1944, the Essex was hit with a Kamikaze with the loss of 16 lives and the Kamikaze pilot.) (10) December 14, 1944: Ens. R. T. Snider's Hellcat from VF-4 went down during a strike on Lingayan Airfield. He was picked up an hour and a half later by the USS Thatcher. (11) December 16, 1944: Lt.(jg) Leonard A. Watson (VF-4) ran out of gas after an attack on airfields in Luzon but reached water to ditch. (See A Kamikaze, a Dogfight, a Splash-Down, and a Typhoon.) His position was reported by his Section Leader and he was rescued by the USS Thatcher. On December 28, 1944, Two Marine Fighter Squadrons replaced our VB-4 Divebombers on the Essex. VMF 124 and VMF 213 were the first two Marine Squadrons to augment carrier airgroups during World War II. Even though this report focuses on POWs, I have listed operational losses from the VMF Squadrons to complete the record. (See War Diary of Two Marine Squadrons.) (12) December 30, 1944: Lt. Thomas J. Campion (VMF-124) flying a F4U "in one of first launchings attempted to climb too steeply from deck and turned to right too soon, spun in off starboard bow. …his belly tank ignited and the blaze was terrific. …he never came to the surface."

(15) January 4, 1945: 1st Lt. Robert W. (Moon) Mullins (VMF-124) was lost on a fighter sweep in bad weather over Formosa. Mullins "became separated in the soup. He was nowhere in sight when the main group broke out about 800 feet over water. He was later heard transmitting by Navy pilots. He was lost, no homing radio, no receiver, no compass. …hit by AA evidently. CAP attempted to locate him and lead him home with no success."

(17) January 6, 1945: Lt. Cdr. Keene G. Hammond, VF-4 Skipper, was lost on an

(18) January 7, 1945: "Exceptionally foul weather" as the Marine F4Us conducted a fighter sweep toward Aparri field in the Philippines. 1st Lt. Robert M. Dorsett (VMF-124) lost in the overcast and crashed into the sea. (19) January 7, 1945: 1st. Lt. Daniel K. Mortag (VMF-124) lost at sea under similar circumstances. (20) January 7, 1945: 2nd Lt. Mike Kochat (VMF-124) also lost at sea. (21) January 12, 1945: 2nd Lt. Joseph O. Lynch (VMF-124) was hit by small-arms fire causing engine failure over Saigon, French Indo-China. "He made a successful landing three miles west of Trang-Bang, …and was last observed, apparently uninjured, standing next to his plane. …It was impossible to conduct rescue operations due to the active antiaircraft positions, however Lt. Lynch is reported to be in friendly hands." With the help of some friendly natives, Lt. Lynch escaped capture and eventually reached the United States through Kunming, China. Part of his "Escape and Evasion Report" makes reference to the fate of Torpedo pilot Don Henry who went down the same day. (22) January 12, 1945: Lt(jg) Donald A. Henry (VT-4) was shot down over Saigon, French Indo-China. Don's crewman was ARM2c E. A. Shirley. A post-war account of his attempt to escape the Japanese and his eventual death is in Torpedo Squadron Four: A Cockpit View of World War II and Saigon Takes Its Toll: A Follow-up Report. The most current information we have on the tragic loss of Henry and Shirley is from Ensign William A. Quinn, who was with Don Henry when he was killed by the Japanese. Ens. Quinn was one of two survivors of a crew of 11 Navy reconnaissance fliers shot down off the Indo-China coast on January 26, 1945.

The Crash--Don told Quinn that he had been burned waiting for Shirley to jump out of the plane. He did not know Shirley had not jumped since he was struggling to keep the plane under control. Don was badly burned. He was placed in a house on the outskirts of Saigon by the Underground, then sneaked into the hospital to be patched up. The Attempt to Escape--Don Henry was escorted by the Free French to a hideout in the mountains where he joined 9 other Americans (including Quinn) and 3 Frenchmen. Quinn and Henry were in the same hut when the Japanese attacked. "Don attempted to run away, went out (the) door, hit in leg, tried to run back asking Quinn to help him. Henry was wearing a white undershirt-an easy target in the moonlight. Quinn was wearing a black sweater. Don was killed by many hits to white undershirt. Quinn was hit in the leg." The remaining Americans had to surrender. They were tied up and forced to sit. The Japanese tried to interrogate them in broken French and Japanese-trying to find out who they were and how they got there. The Japanese started a fire with the contents of the huts, tore off the bamboo door and threw it on the fire. The Japanese commander paced back and forth, interrogating them for about an hour. Suddenly, without warning, the Japanese took someone from the other end of the line to the side of the hut and beheaded him. Then they took Tommy. Tommy screamed, "No! No!" Shouting and screaming the men were decapitated one at a time. Quinn tried to get up-screaming and crying. He was hit in the back of the neck with a rifle butt. (Note: "Tommy" in this recounting remains unidentified to date by the author.) Suddenly, the executions stopped. Two Americans remained alive-Ens Quinn and Vincent Grady. Quinn learned later that the Japanese beheaded two Americans for every Japanese killed in the surprise attack. The two survivors were sent to a prison camp in Saigon and were released after the Japanese surrender. Quinn brought back this story and stated, "Don was a hero!" (23) January 15, 1945: Air Group 4 Commander George Otto Klinsmann was lost

"Commander Klinsmann picked the DD as a target for his division, scoring two rocket hits himself just aft of amidships. …Immediately after this attack, Commander Klinsmann`s plane (F6F) was seen covered with oil from an AA hit. His division started back toward base. Due to low oil pressure, Cdr Klinsmann decided to make a water landing near two dispatched US picket destroyers rather than depend on his plane flying the additional 50 miles over rough seas. His wingman went over the forced landing check-off procedure and got a thumbs up on each item. …The Commander made a perfect water landing, was observed to abandon and clear his plane before it sank…..One of the DDs reported having Klinsmann in sight, successfully throwing him a life line with a life buoy ring attached, and as he was pulled alongside and about to be hoisted aboard he lost his grasp on the ring, floated clear of the bow and sank before the DD could position itself again. The DD reported that neither Cdr Klinsmann's life jacket or life raft were inflated." As the operations report states, "Commander Klinsmann`s loss was unexplainable …unwarranted." (24) January 16, 1945: Three torpedo planes from VT-4 were forced to make water landings after a strike on Hainan. (1) Ensign William F. Walker with AOM2c G. F. Zeimer: (2) Lt. Edward S. Binder with ACMM R. C. Biddle and (3) Lt(jg) Gerald W. Thomas with Amm3c Donald H. Gress and PhoM3c Robert B. Montague. Binder and Biddle were picked up by the destroyer USS Callahan and the other pilots and crewmen were rescued by the destroyer USS Sullivans. (See In The Drink in Torpedo Squadron Four: A Cockpit View of World War II for a report on this strike and rescue.) (25) January 16, 1945: 1st Lt. George R. Strimbeck (VMF-124) was lost in a dogfight with Japanese Zekes during a fighter sweep over Hainan. The War Diary states: "Lt. Wastvedt slid out to starboard so they could start a section weave, but Lt. Strimbeck (apparently excited) turned away from him in a tight 180-degree turn, leaving the enemy with a perfect no-deflection shot. The Zeke hit his belly tank, and Strimbeck`s plane immediately burst into flames. The pilot bailed out and was seen parachuting downward." A rescue sub was vectored to the location of the downed pilot but there were no reports on a later rescue. Listed MIA. Note: "The Zekes that intercepted the VMF fighters belonged to 901 Kokutai (or Ku) stationed at Samya Air Force Base, Hainan. Three Zero pilots were lost in combat on January 16, 1945. KIA: Lt. Tsunekata Maki (Naval Academy 71), Lt(jg) Shungo Shiroto (N.A. 72), and CPO Hajime Tsuji (Otsu 9). CPO Tsuji's surname also could be read as Toji, Miyaji, Tochi, or Miyakoji. 901 Ku was organized on January 1, 1945." (Thanks to Mr. Minoru Holmes Kamada, Tokyo, Japan, for providing this information.) (26) January 21, 1945: Strikes on Formosa. "At Miyako Jima, Lt(jg) Robert W. Ginther (VF-4) was caught in an explosion of his own bomb as he attacked a ship, and was killed." The same day, "One plane flown by 2nd Lt. John T. Molan made a forced water landing and was picked up by the USS Caperton." (27) January 21, 1945: Ensign Frank H. Bissell, Jr. (VT-4) with ARM3c William H. Moore were lost over Amami O Shima. "During the attack, Ensign Bissell made a shallow glide over the airstrip (Kikai), descending below 1000 feet. As he retired, his plane was burning. The plane continued low across the island and appeared to be gliding for a water landing. The plane, however, crashed into the sea and sank instantly. …VT circled the spot but saw no survivors." Note: Mr. Minoru Holmes Kamada provides the following information about this strike: "At 8:40 am, 18 carrier planes suddenly appeared over the north eastern beach of the island. The formation divided into two flights and one of them made strafing runs against the airfield, bay, and Agaren (or Akaren) village. The planes also dropped bombs in the center of the town. The casualties from the first flight were five people killed, one wounded, and several houses destroyed. The second flight dropped bombs and strafed Kizutsu village. 18 people were killed or wounded and 10 plus houses were damaged." (These details based on written memories by several Amami O Shima islanders.) Mr. Kamada has not found any records on the capture of Ensign Bissell, Jr. or ARM3c Moore. (28) February 16, 1945: Mawatari, Japan. Lt(jg) W. C (Dusty) Rhodes (VF-4) lost over Japan, during dogfights. "Taylor, Schulden, and Rhodes fell behind due to engine trouble in Rhodes' plane and were attacked by about 10 planes. In the ensuing scrap, Taylor downed three, and Schulden and Rhodes one each, but Rhodes' plane was smoking. As the three retired, Taylor and Schulden were kept busy by the harassing Zekes… and Dusty Rhodes disappeared. Nothing is known of his whereabouts." No post-war information has developed. (29) February 17, 1945: Continuous strikes on the Japanese mainland. No casualties but Hellcat pilot C. E. Gustafson from VF-4, "…was forced to make a water landing because of a hydraulic leak and electrical failure and was picked up by the USS Callahan."

Note: Mr. Minoru Holmes Kamada, Tokyo, Japan, provides the following translation of the G.H.Q. document on Carlson's capture: "At seven in the morning of February 25, a F4U from the Essex crash landed in a rice field in Kami-Otsu town (which is the city of Tsuchiura today). Carlton was captured by local volunteer guards and was handed over to Tokyo Kempeitai. For 40 days he was questioned at the Kempeitai Office before he was sent to the Omori POW camp in Tokyo." (31) March 1, 1945: In strikes on Naha airfield on Okinawa, AG-4 lost our artist fighter pilot Lt(jg) Douglas R. Cahoon and a Torpedo plane piloted by Lt(jg) C. N. W. (Scott) Vogt with AMM2c R. E. Kelly as gunner. Debriefing reports state, "In the last attack, Lt(jg) Cahoon disappeared and has not been recovered. Members of the division reported that he was with the flight just as they commenced their last strafing run of the day and failed to join up when the group rendezvoused west of the airfield over the sea." (Note: A complete report on the loss of Cahoon is available in The Lost Pilot/Artist.) The report on Scott Vogt states, "As Lt(jg) Vogt dropped his bombs, the first three or four were seen to release in train and then the remainder fell in salvo, exploding approximately 100 feet below the plane. The after-part of the plane was blown off and the plane spiraled left. One parachute was observed to open over target at approximately 6000 feet. …A search was conducted by two OS2Us from the USS Astoria with fighter escort from the Essex over the waters near the target, since it might have been possible for the parachutist to have drifted over water. Results of the search, however, were negative." Most of us who saw the plane explode believe it was Vogt who hit the silk, but "It is highly possible that, as the airman drifted down, he served as target practice for the Japanese machine guns." March 1, 1945 was the last combat mission for Air Group 4 in the Pacific. (32) Four additional pilots attached to Fighting Squadron 4 (VF-4) are memorialized in the book Fighting Squadron Four: The Red Rippers by Lt. Clifford M. White and fellow pilots of VF-4. Only sketchy details of these losses are available at this time:

Footnotes: Material in this article is taken from US Naval Combat and Operational Reports, private dairies, interviews by the author, and other sources. The author would appreciate being notified of any deficiencies. It is important that due recognition be given to all those who made the supreme sacrifice in the service of our country during World War II. The photo of Lt(jg) John H. Palmer at Stalag Luft III is provided by John J. Mulligan, Jr., nephew of Lt. Thomas E. Mulligan. |

|

Air Group 4 - "Casablanca to Tokyo" |

|||

|

|

|||