|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

We Survived |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Bernhard A. E. Nolte |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

It was the 26th of September 1943, a beautiful day in the fall. The sun was good to us, probably out of compassion for us, young 17-year-old soldiers, who were on their way to battle for a cause, whose origin we did not understand entirely. But they did their best to make us believe in it. The ship was anchored at the quay and we climbed on board over the gangway in order to, according to commands, "disappear" into the bowls of the ship. Our destination or our marching orders were only known to those who were supposed to lead us. Of course, lots of rumors about our possible deployment or operations theater were making the rounds through our ranks. It was known among ordinary soldiers as "latrine scuttle butt." We had left our four-footed friends and comrades behind in Denmark and so we believed that our destination was the Russian front. New horses would surely be available in the horse country of East Prussia. New rumors swirled. Transported by sea, the Baltic Sea to East Prussia, probably by the harbor of Danzig. That made sense. The loud rumble of the ship's motor indicated that the trip by sea had started. The soldiers, who just a short time ago were mere civilians, who had never considered the sea as an element, and not even ever considered the size of a ship, suddenly were faced with nature and natural forces. The ship "rolled," according to sailor's terminology, and the waves did not allow a tranquil trip. The best place to be was under, in the hold, on a bunk bed, where you slept, or at least tried to sleep, the sleep of the righteous. And, surprisingly, it worked. A shrill whistle is the usual way to wake you up from a restful sleep and start the orders of the day with "the Prussians." My first thought was I had to go and tend to the horses, feed them, water them, curry them, so I jumped from my bunk. Instead of morning roll call, "coffee carriers fall in," breakfast. It was a completely different form of "morning prayers" than we had had up to now in our training. Those who could went on deck and came back with the news that they had seen lots of mountains on the coast. Well, from our geography lessons, we did not remember any mountains or rock formations on the coast of East Prussia or on the Baltic Sea. But where were we? The more experienced among us, those who had followed all the battles of the German Wehrmacht, were convinced this should be Scandinavia, say Norway. But what should we do with our training as horse soldiers, every day for 125 days, from morning until night, in this land of mountains? As infantry soldiers we were a disaster when it should come to a firefight. We hadn't even learned how to shoot at a still target. But what then? We were in Norway and we disembarked in Moss, a harbor east of Oslo. Equipment or heavy weapons we didn't have, only the so-called "bride of the soldier," our 98K rifle, caliber 7.1 mm. We marched into a requisitioned school, made a makeshift command post out of it, roll call, distribution of rations, weapons care, uniform parade. There is always some sort of roll call with "the Prussians." Soldiers should not be allowed to think too much. In the Cavalry we have a saying: "Leave all the thinking to the horses. They have a bigger head anyway." The comrades took advantage of the few minutes rest to talk about the new place they had arrived at. The sword of Damocles was still hanging above our heads, but we had skipped the bitter chalice of "deployment to Russia" for now. We did not make much of the Army using us as Cavalry in Norway, because we didn't have our four-legged comrades anymore. After the end of the day at 1800 hour: whistles, commands: "Everybody out for roll call," yelled the NCO. After the usual military foreplay during the parade, "Attention, eyes right, line up, eyes front, as you are," came the announcement: "At 2000 hours this unit will present itself ready to march off in front of the building. In 30 minutes you will receive marching provisions as per each Cavalry section (12 riders to one section) for 3 days. Any questions? None. Ten'shun. To the rooms, break ranks." Now it was not especially a pleasure cruise, even if we had survived the trip by sea during our sleep and with very little disturbance. In the Army everything makes sense or nonsense. At 2000 hours the entire crew was standing outside. Then the presentation, "Marching company ready to march off." Again that absolutely necessary, "Right turn, same step march...." Where to? Horse soldiers in a marching column are not what you call a "piece of jewelry." Their marching formation is with horses, sitting straight up in the saddle. And now, the two saddle packs, normally hanging left and right on the saddle, have to be carried on your back. Then there are the great coat, the bed cover, the tent ground cover normally rolled up and fixed to the horn of the saddle (now carried on top of those unsightly saddle packs), the "bride of the soldier" (the rifle) hanging from your shoulder, while the crease resistant cap (the steel helmet) is dangling from your belt. Count to all that the special high riding boots with spurs and the pants with that stubborn leather patch on the behind. The marching formation arrived at the train station and we all crawled into the freight cars. There were other young soldiers in the freight train, but we had no idea where they came from. We just couldn't care less. There was no straw anywhere in the freight cars, so we simply dropped on the floor. Then a whistle from the locomotive, a hard tug and the trip started to the north through the night. In some of the freight cars the doors were wide open and we heard some nice singing. The crew in our car was triggered by it and one of the soldiers tuned in "Therefore girl please do not cry, I am called by my holy duty, because I must accompany my brother, to fight for the Fatherland and for Freedom... " The monotone noise and the repetitive click-clock of the wheels on the rails finally brought us some restful sleep. A soldier was programmed in such a way that he could fall asleep anywhere and in any position. At daybreak the first comrades woke up early, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. The sun was smiling from the sky, but the beauty of nature, of the land that slid by, did it interest us? Were we apathetic? How come? In the afternoon the freight train arrived at a freight yard. Where were we? Unknown, until somebody discovered a sign with "Trondheim" on it. We tried to sort out what and where Trondheim was, until again we got that dammed whistle and that yelling and the snarling commands: "everybody out and line up in marching formation on the opposite site of the rails, march, march." March, march was the way to say "get the lead out, on the double." Those who had left their ruck sacks intact during the trip and simply had slept on the floor, didn't need any more encouragement to increase the speed of following this command. We stand in formation, again, "right turn, as you are, march." We sort of walked through the streets and without any thought that we might be observed by anybody. We arrived at a building that belonged to the Salvation Army, a meeting and prayer place. "In single file, fall in." We saw a room in subdued light, with a rather worthy atmosphere. Everywhere prayer books, religious artifacts, a choir loft, prayer benches, which gave us our impression of the place. The next day, October 3, 1943, started with the same "ceremony" as always in the Prussian army. Only today everything was earlier. This means the wake up call was not at the usual 0600 hours, but rather at 0400 hours. At the morning roll-call, we got the extra command: "Clean your quarters and get ready to depart, we leave at 0700 hours." So we had to bury the hope that we would make our home here in Trondheim. "According to the wishes of our NCO," the crew was ready by 0700 hours, after we had cleaned the quarters painstakingly and after we had put all the "prayer books and pious documents" in their correct places. Without the usual song, the column marched off, destination unknown. But soon we saw water, a fjord, close by. The march ended in the harbor, at the quay. There laid a steamboat called the Skramstad. With an "everybody climb on board," we obediently did so. Did we have to go further north or had our fearless leader gotten second thoughts and wanted us back? Were we -- and a soldier, when he doesn't know exactly what is going on, starts spinning tales -- were we maybe part of the invasion troops against England? Latrine rumors, latrine rumors. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

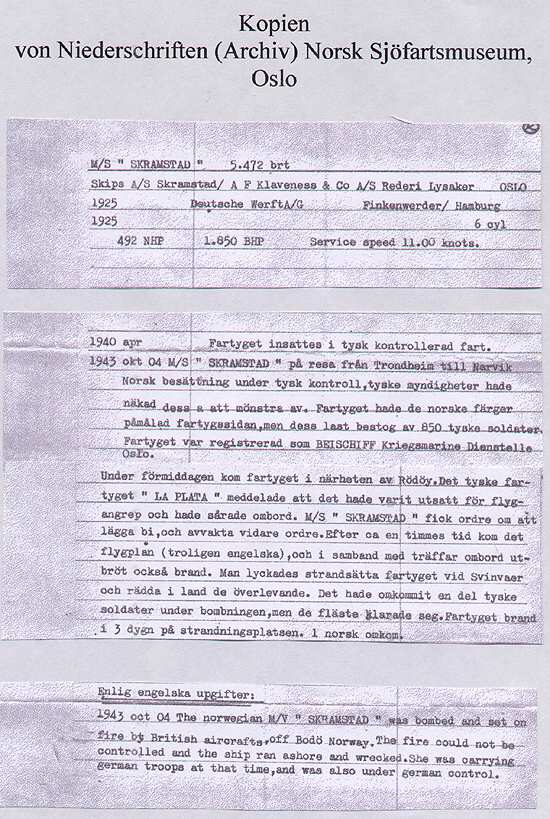

Ship´s Log -- Skramstad |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The part of the records regarding the operation of the Skramstad during WWII reads as follows: 1940 - April - Freighters are put under German control. 1945 - October - The M.S. Skramstad sailing from Trondheim to Narvik, Norwegian ownership under German control - German authority has sanctioned the trip. The freighter had the Norwegian flag painted on its side. The last freight consisted of 850 German soldiers. Freighter was registered as supply ship for the Kreigsmarine Dienststelle Oslo. (German War Navy Office Oslo) In the early morning the freighter arrived in the vicinity of Rödöy. The German freighter "La Plata" signaled it had come under attack and had wounded on board. The M.S. "Skramstad" got orders to stand by. One hour later airplanes, (supposedly English) bombed and strafed. Fire broke out on board. But luckily they were able to beach the ship and put the survivors ashore. Several German soldiers perished because of the bombing, but most of them survived. The freighter burned for three days and nights on the beach. One Norwegian lost his life. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Our space on the Skramstad was in the front, in the bow of the ship. A small room, about 10 by 15 meters, (30 by 45 feet) with a separate entrance -- door and wooden ladder -- down. Bunks were nowhere in sight, one sat down where one stood. This cell was just enough for us, 75 to 80 Cavalry soldiers. Nothing moved below deck. And we were told to stay down there, because of possible enemy intelligence. The sun rose in all its glory on the horizon, a weather so calm, to "lay eggs in." One single ray of the sun sneaked through the door to us below there, in our "dungeon." We whiled the time away by doing nothing; we slept or we played cards. Motto: "To the soldier it is a royal pain, because half his life he lives in vain." They had to allow us to do what we wanted, because of the lack of space on board. The sudden shrill whistle this time was welcome interruption of our boredom, because the accompanying command sounded like "Get ready for chow." That elicited a lot of movement and activity among the troops. Mess kits were dug up and we had sudden illusions of a mess kit filled to the brim with pea soup. And indeed, we climbed up the ladder in single file and we were really conducted towards a field kitchen that we normally called a "goulash cannon." Nowhere could you find such a tasty pea soup than in the Prussian army, even if everybody seemed to believe that, to keep you calm, they put some camphor in it. After the meal, back below deck. At about 1300 hours (local time) the steamer moved again. Seemingly the "voyage" continued. After a certain time, the "curfew" was lifted and we were allowed to go on deck. All around us was water and we saw with glee that one of our drill sergeants was hanging over the railing, feeding the fish, or more profane, he was vomiting. Hours went by and the Skramstad did what it was supposed to do. From the position of the sun and the time, we could tell we were going due north. What was there, who or what needed us there? The monotonous voyage, only water, and as a variation, on starboard or both sides, high rock coasts, caused us to go down below deck again, to do what we were doing before. A new day, October 4, 1943, appeared. It could have been around 0930 to 1000 hours local time when on the port side we suddenly saw a steamer burning. Our own convoy stopped and from the burning steamer, which we recognized as the La Plata, we were asked by light signals if we had a doctor on board. We hardly came to understand what had happened when we heard our familiar whistle and the command "air raid alarm, everybody below deck." We hastened down the ladder. Air raid alarm under the circumstances didn't mean anything good. Then we heard somebody yell "life jackets." Up to now, we hadn't heard anything about life jackets. Then we heard, "What do we need life jackets for, we good, healthy soldiers born in the year 1925?" (Pure idiocy, of course.) But the yelling stopped right away, because the "music" started. Somebody strafed our ship with machine gun fire, and we could hear the sound of the shooting and see sparks through the trap door. A detonation outside the ship somewhere in the water provoked a huge wave that splashed against the side of the ship. "God punish England and the damned Allies," was the answer of the soldiers. (That was a chosen and meaningless expression a soldier would always use when something became adversary to him during his training.) We didn't have to wait long after this swaggering because a tremendous bang, a burst, made everything tremble. The light went out, darkness, even the sparingly small opening of the trap door. Dead still, outside also. Somebody had caught our Skramstad, we were hit. I found myself without any luggage, just my steel helmet, climbing the ladder and I faced a captain with a pistol pointed at me point blank. He motioned me with the pistol and in a loud voice he commanded me to go midships. I climbed over the destroyed field kitchen, (which had unfortunately spilled its contents -- the pea soup -- all over the deck) over the mid-hatch, through the fire and the smoke, and I suddenly found myself at the gangway. Without any emotion, without really thinking about anything, no fear or questions, I ran down the gangplank into a lifeboat. Next we were dragged, together with two other lifeboats, away from the ship by a motorboat towards a rock island about 200 meters away. During that short trip our lifeboat was dangerously taking on water, because its air filled floating pontoons were all riddled with bullet holes. My steel helmet served us well as a water scoop and we arrived, a bit wet, on the saving shore. A glance at the Skramstad showed a sad picture. The gangplank was afire. At the bow, many ropes were dangling and lots of my comrades tried to lower themselves down to the lifeboats. Not so smart and mostly dutiful comrades tried to carry their complete equipment with them, including the heavy rifle and, because of being overweight, they came down faster than they wanted, hit the comrades below them, and everybody ended up in the drink. We heard ominous explosions on the Skramstad. Less and less comrades used the still open road to safety. On top of that, we heard the noise of an airplane above us. Thank goodness, it was a German one, who was probably observing and documenting the event. About 110 to 120 comrades were stranded on those rocks. It was our home until 2400 hours that night. Before us the red glow of the burning Skramstad. We were rescued by a steamer from the Hurtig line who brought us to Bodö. Goodbye comrades, you who will stay forever on the Skramstad. We survived. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

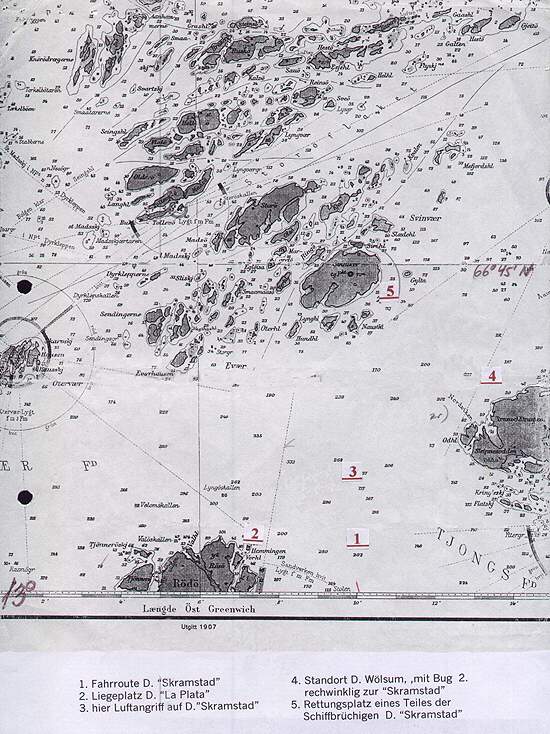

Map showing route of the Skramstad. Legend: |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Air Group 4 - "Casablanca to Tokyo" |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

We, the recruits of the Replacement (Ersatz) Company of the Infantry-Cavalry Riding School Number 6, Field Post Number 04740 E, were in a state of readiness for front service. We had already passed through the assembly camp at Roskilde in Denmark and were now waiting in the harbor of Copenhagen to be shipped by sea.

We, the recruits of the Replacement (Ersatz) Company of the Infantry-Cavalry Riding School Number 6, Field Post Number 04740 E, were in a state of readiness for front service. We had already passed through the assembly camp at Roskilde in Denmark and were now waiting in the harbor of Copenhagen to be shipped by sea.