|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Tribute to Avenger Air Crewmen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Gerald Thomas |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The sacrifices, extraordinary courage, and discipline of the men who occupied the turret and belly positions of the Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger during WWII have never been properly acknowledged. Nor were they awarded the appropriate medals to partially compensate them for their bravery. Citations for successful strikes usually went to the pilots while the crew served without recognition. The TBF was designed to carry two crewmen. One occupied the turret and the other was stationed in the belly or tunnel. Neither crewman could access the pilot's cockpit because of the armor plate behind the pilot's seat. The turret gunner faced aft and manned a .50 caliber machine gun. The tunnel, encompassing about half the total airframe, was equipped with a bench seat, radio, radar (later in the war), and other mechanical equipment. There was a .30 caliber machine gun facing aft below the tail. The tunnel did not provide much comfort. "It was noisy with limited visibility. After days of intensive combat, it became encrusted with and smelled of engine oil and transmission fluids. It could produce a discouraging claustrophobia for the uninitiated." (1) As the war progressed in the Pacific, enemy fighters rarely made low-side runs and the belly gun was not needed. Also, there was very little armor protection in the belly, putting this crewman in constant danger of shrapnel wounds from A/A fire. Thus, most torpedo squadrons started carrying only one crew member in each TBM. This crewman would occupy the turret most of the time, but could slide down into the belly if needed for radio adjustment, arming bombs or torpedoes, etc. The exception to the one crew member rule was made if a photographer or news correspondent was assigned to the strike. Riding backwards in the turret while sweating out a torpedo run or glide bombing attack in the belly of a TBM required a special kind of courage. Crewmen watching tracers or parts of the cockpit hatch stream by never knew if A/A fire had killed the pilot or if the plane was out of control. The few seconds of push-over, dive, and questionable pull-out seemed like an eternity to the crew. "One time over Manila, I thought Scott, my pilot, had been hit. It seemed that he would never pull out--we just kept going down. I thought he was dead, so I snapped on my parachute, kicked the hatch, but it wouldn't open (I was too excited to pull the pin). About that time, Scott pulled out" -- Leo Halvorson, VT-4 Crewman "I was flying with Cole on a Formosa strike. The CO found a hole in the clouds, and we went in. The first planes cleared with no problems, but we were on the tail end of the formation. The A/A fire was increasing and the Plexiglas was shot out of our plane. I looked at those mountains, and I didn't want to jump… We iced up on the return trip to the Essex." -- Noel Shiverdecker, VT-4 Crewman "We were in a dive on some Japanese ships and the engine skipped. I thought, 'My gosh, here we go!" and looked for a spot to bail out" -- Stan Coller, VT-4 Crewman There are many other examples of crew reactions during strikes against enemy shipping and shore targets. Bail-Out Problems The Grumman TBF Avenger has achieved a higher level of publicity since George Bush became President of the United States. Also, more attention has been given to the problems of crew bailout during WWII. Several examples of the problem are cited here. First a brief summary of the fate of Lt(jg) George Bush's crew members. The combat debriefing report from the Naval Archives states as follows: "After releasing his bombs, Lt(jg) Bush turned sharply to the East to clear the island of Chichi Jima, smoke and flames enveloping his engine and spreading aft as he did so, and his plane losing altitude. He advised the CO by radio that it was necessary to bail out. At a point approximately 9 miles bearing 045° from Minami Jima, Bush and one other person were seen to bail out from about 3,000 ft. Bush's chute opened and he landed safely in the water, inflated his raft, and paddled farther away from Chichi Jima. The chute of the other person (either Lt(jg) White or J. L. Delaney, ARM2c) who bailed out did not open." Keep in mind that neither the turret gunner or the belly gunner/radioman can wear their parachutes during operations. The man in the belly has to snap on his chest pack chute and crawl out the small door against a fierce airstream while the turret gunner drops down into the belly to follow suit. All this takes valuable time if the plane has been hit with anti-aircraft fire. It appears likely that the individual in the belly of Bush's TBM cleared the plane but not in time for his chute to open while the turret gunner failed to clear the burning plane. I learned about the difficulties of crew bailout as a pilot of a TBF Avenger during a strike against German shipping along the coast of Norway on October 4, 1943. Our 9 Avengers were loaded with four 500-pound armor-piercing bombs for maskhead-level attacks on Nazi ships. The plane in front of me, flown by Lt(jg) John Palmer, received a direct hit from A/A fire. Palmer bailed out but his two crew members went down with the plane. We do not know whether the crew were killed in the plane or whether they had insufficient time to bailout. Palmer spent the remainder of the war in Stalag Luft III as a POW. A few minutes after Palmer was shot down, my TBF took a 20mm shell in the engine. After a brief flash of fire, the engine started smoking and oil covered my canopy. With Palmer's burning plane fresh in mind, I climbed to about 1,000 ft and ordered the crew to bail out. I thought both of my crew were out when Garner, my turret gunner, called frantically to inform me that he couldn't get out. He said, "Jackson has popped his chute in the belly and can't get out the hatch!" The spring-loaded silk had let loose inside the plane. Jackson tried several times to bundle the slippery silk in his arms and work his way through the narrow hatch. But no such luck, he and Garner were trapped. I told the crew to settle down. We would make a water landing in fjords. Concentrated anti-aircraft fire soon convinced me to change my mind. That trusty Avenger, with the engine still smoking, carried us back to the USS Ranger, where I crash-landed. Torpedo 4 was transferred to the Pacific in October 1944 where we operated from the USS Bunker Hill and the USS Essex. The Avenger with dedicated crew members served us well, as we made torpedo runs and glide-bombing attacks on Japanese shipping and shore installations from the Philippines to Iwo Jima and Okinawa and all the way to Tokyo. However, the problem of crew-bailout continued to haunt us as, on several occasions, we observed only one parachute emerging from a doomed TBM. After my Norway experience, I resolved, if at all possible, to stay with the plane. Another challenge for my crew members came when I was forced to ditch in the South China Sea after a strike in Hainan on January 16, 1945. Two other VT-4 planes also made water landings due to fuel exhaustion after this attack. For more details, see Chapter 25 of Torpedo Squadron Four: A Cockpit View of World War II. When it became obvious that the fuel remaining in our Avengers would not carry us to a rescue destroyer, I called my crew on the intercom to prepare for a water landing. Don Gress was in the turret. Don and John Holloman, as regular members of my crew, took turns as turret gunner. It was Holloman's turn to stay on the carrier. Robert B. Montague, a Navy photographer, was in the tunnel. This was Montague's second hop with me. He was assigned to cover the Hainan strike with both movie and still cameras, but he had not bargained for a splashdown. Before the water landing, I asked him to climb from the belly into the area behind the pilot and to face backwards during the landing. I also asked him to grab a couple of extra survival kits that were stowed in the belly and to get ready to release the escape hatch after we were in the water. I turned into the wind and made a wheels-up, full stall landing. The splashdown was not much harder than a normal carrier landing, although the plane was completely submerged for a few seconds. Montague and I jumped out onto the right wing as the plane came to the surface. We pushed the large raft that was stored in the fuselage over to Gress, but he was washed off the wing before he could get it inflated. Montague and I inflated a small raft, then we too, were washed off the wing. As we floated under the tail of the plane, I thought it would drag us down as it sank. While I was fighting to get clear of the plane, Montague was taking pictures with a small camera that he had managed to salvage.

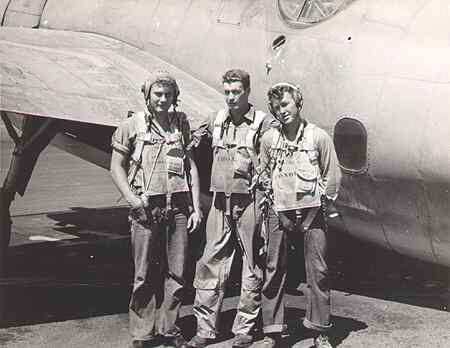

As we prepared to ditch, I called the code name of the picket destroyer with my position. I received a Mayday acknowledgement, and later that afternoon we were rescued by the USS Sullivans. This destroyer was named after the five Sullivan brothers who were lost when the USS Juneau was sunk by the Japanese on November 15, 1942. After our rescue, I gave the Skipper of the Sulivans the approximate location of the first Avenger that went down. The destroyer preceded to that location and after a circle or two, picked up Willie Walker and his crewman G. F. Zeimer. The third TBF from Torpedo 4 to splashdown that day was piloted by Ed Binder with R. D. Biddle as gunner. Binder and Biddler were rescued by the destroyer USS Callahan. Whether in a splashdown, a barrier crash, a torpedo run, or a glide-bombing attack, the aircrewmen of VT-4 and other Torpedo Squadrons carried out their assignments without complaint and in the highest traditions of the US Navy. Certainly they deserved more medals than the few that were dispensed by the Navy during WWII. Additional Notes About My Flight Crew My flight crew during our tour of duty in the Atlantic Theater consisted of C. P. Jackson (ADM2c) and S. E. (Earl) Garner. Garner was the turret gunner and Jackson ran the radio and bombing gear from the belly of the TBF. When Air Group 4 returned to the East Coast and reformed for the Pacific, Jackson and Garner were reassigned and I lost contact with them.

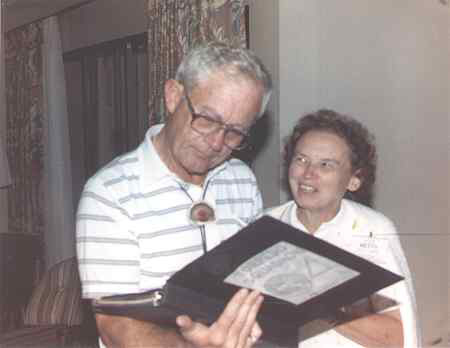

Don Gress and I kept in touch after the war and we both were active in the Torpedo Four Reunions. After mustering out of the Navy, Don became a tool and die maker. He passed away on November 24, 1999.

(1) William B. Chase. "The Cheap Seats" in Avenger at War by Barrett Tillman. Charles Scribner´s Sons, New York 1980. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Air Group 4 - "Casablanca to Tokyo" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||